“Nothing is harder to understand than a symbolic work. A symbol always transcends the one who makes use of it and makes him say in reality more than he is aware of expressing.”

Albert Camus

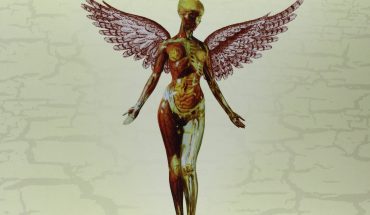

The Holy Bible arrived on 29 August, 1994 – the same day Oasis’s Definitely Maybe was released and almost five months after Kurt Cobain ended his own life. In hindsight both events were significant for Manic Street Preachers: the Nirvana singer’s suicide deeply affected the album’s principal lyricist, Richey Edwards, and almost certainly influenced its harrowing tone, while the Manchester band’s huge popularity would soon bring indie guitar bands to the masses, and provide the opportunity for the Welsh band to reach a wider audience beyond its loyal fan base after Richey disappeared. Yet although Everything Must Go and This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours brought the Manics their greatest commercial success – and the stadium rock status they had long coveted – The Holy Bible remains their masterpiece.

Naming an album after a sacred religious text would seem utterly ridiculous in the hands of most bands; here the title demonstrates the extent of the Manics’ ambition, zeal and absolute belief in what is, essentially, a manifesto to explore the history of politics and human suffering in the 20th century. The 13 songs on The Holy Bible reveal a band at the peak of its powers, both musically and lyrically. The album possesses that rare quality in pop music, where the combination of words and music are in perfect alchemy. It’s not an easy listen; the magnitude of the themes explored – oppression, fascism, the Holocaust, revolution, mass consumerism, anorexia, self-mutilation – are mirrored in the precision and ferocity of the post-punk/industrial sound. Tellingly, the album’s desolate outlook may also be seen as a reflection of Richey’s personal decline, though speculations on his mental state and subsequent disappearance are best left to those who knew him. This is about the record.

Opener ‘Yes’ begins with a sample of dialogue from a documentary about the sex trade (“Everything’s for sale…”) and imagines the struggle of a prostitute: “In these brave streets of pity you can buy anything/For two hundred anyone can conceive a god on video.” It sounds like one of the band’s most upbeat and immediate pop songs, but don’t be fooled: its suitability for radio is scuppered within four words of the first verse: “For sale? Dumb cunt’s same dumb question.”

‘Ifwhiteamericatoldthetruthforonedayit’sworldwouldfallapart’ (a quote from American comedian Lenny Bruce) attacks the racism of US gun laws and is remarkable for the way James Dean Bradfield manages to wrap the grandiloquent lyrics into a melody: “Compton, Harlem, a pimp fucked a priest/the white man has just found a new moral saviour.” This ability to craft catchy and memorable melodies from what are often miniature essays is one of the album’s most striking features. It’s evident again in the relentless punk-metal assault ‘Of Walking Abortion’, a study of how the weakness of man is a chief cause of fascism:

Little people in little houses

Like maggots small blind and worthless

The massacred innocent blood stains us all

Who’s responsible – you fucking are

‘She is Suffering’ is one of the album’s less intense moments, and provides respite before the harrowing ‘Archives of Pain’, an attack on society’s fascination with serial killers that argues in favour of capital punishment and the sterilisation of rapists. The unflinching lyrics are evidence of the band’s complex moral code, which goes beyond merely sympathising with the victim to actively seek vengeance: “If hospitals cure, then prisons must bring their pain/Do not be ashamed to slaughter, the centre of humanity is cruelty.” Moving from the personal to the political, the next song captures the band’s unique ability to fuse frenetic Ramones-style punk pop and political discourse. ‘Revol’ name checks a list of Russian Presidents to speculate on their sexual foibles:

Mr. Lenin, awaken the boy

Mr. Stalin, bisexual epoch

Kruschev, self-love in his mirrors

Brehnev, married into group sex

Gorbachev, celibate self-importance

Yeltsin, failure is his own impotence

To those familiar with Richey’s struggle with anorexia, ‘4st 7lbs’ needs little explanation. One line is particularly haunting: “I wanna be so skinny that I rot from view/I want to walk in the snow and not leave a footprint.” The song makes for uncomfortable listening given the series of events that followed the album’s release, though removed from this context it is no less startling for its unflinching and detailed exploration of its subject matter.

If the vibrant new wave guitar intro to ‘Mausoleum’ seems at odds with the bleak title, then the opening lines soon set the morbid tone of the song, an attack on Holocaust denial: “Wherever you go I will be carcass/Whatever you see will be rotting flesh. Along with ‘The Intense Humming Of Evil’, which recounts the evil of German concentration camps from the viewpoint of the victims, it’s one of the album’s darkest moments as befits the subject matter.

‘Faster’ is arguably the definitive Manic Street Preachers song (rivalled only by ‘A Design For Life’). It opens with a sample of John Hurt in 1984 (“I hate goodness, hate purity”) before a PiL-esque sonic assault of distorted guitar and pounding bass and drums kicks in. With lyrics that address self-abuse and a chorus that declares “I am stronger than Mensa, Miller and Mailer/I spat out Plath and Pinter”, its meaning may be somewhat opaque, though it’s undeniably one of the band’s most powerful songs.

The next two tracks both look at memory and the passing of time, albeit from markedly different perspectives. ‘This Is Yesterday’ is something of an anomaly on the album, in that it’s the closest thing to a ballad. Written by Nicky Wire, the song looks at the concept of nostalgia and our tendency to imagine childhood as the happiest period of our lives. ‘Die in the Summertime’ is less winsome and told from the perspective of someone for whom memories of youth merely torment in the present: “Childhood pictures redeem, clean and so serene/See myself without ruining lines.” Within a year of the album’s release, the title would seem almost prophetic.

With its rousing sprint-to-the-finish-line punk rock tempo, album closer ‘PCP’ bears the hallmarks of early singles like ‘Motown Junk’, ‘Stay Beautiful’ and ‘You Love Us’, and warns against the inherent dangers within a culture of political correctness: “Systemised atrocity ignored/As long as bi-lingual signs on view.” The sample of Albert Finney dialogue from The Dresser adds extra poignancy (“227 Lears… and I can’t remember the first line”) given the fate of Shakespeare’s tragic king, and provides a fitting end to the dystopian vision of The Holy Bible.

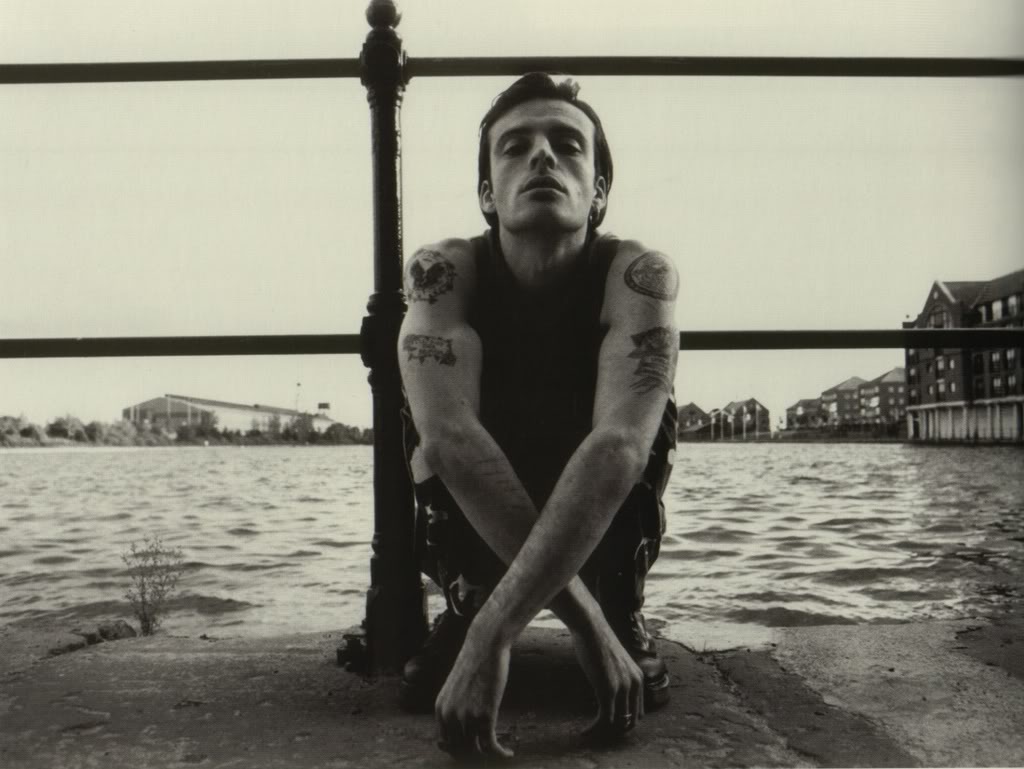

In the aftermath of Richey Edwards’ disappearance, the album’s reputation has grown with each passing year. To romanticise Richey as the doomed poet/artist destined for self-destruction is degrading, not only to his band mates and loved ones, but also to this formidable record, which ought to be celebrated as a triumph and not lamented as a suicide note set to music. And while to some he is remembered most for carving ‘4 REAL’ into his arm during when the band’s authenticity was called into question, or as the tragic rock star who abandoned his car at the Severn Bridge, for me his legacy remains the 56 minutes and 17 seconds of The Holy Bible and the brilliant intellect behind this remarkable album. No one else before or since has articulated the pain of human suffering on record with such beautiful menace and ferocious intelligence.

Paul Sng