Colin Vearncombe tells Dave Sedgwick about brushes with Euro stalkers, Fame and taking care of the tribe.

“Some men are born great, some achieve greatness”, wrote Shakespeare, “and some (quoth the bard) have greatness thrust upon ‘em.” He was right of course. Take the music biz as an example. One minute it’s indifference and ingratitude down the Pig and Whistle with nought but the promise of a grope of the bassist’s sister to sustain your rock n’ roll dreams, the next minute and wham, you’re on the telly, sat next to Noel Fielding being all witty and irreverent.

That’s sort of what happened to a shy, impossibly young-looking kid from Liverpool back in 1987. Granted Never Mind the Buzzcocks might have been before his time and there isn’t to my knowledge a Pig and Whistle in Liverpool, but you catch the drift. It can all happen in a whirl.

At an age when most young bucks are doing the rites of passage stuff, here was a young man who spent his time composing songs that reflected upon life’s vagaries, explored its paradoxes. Sure there might have been a passing resemblance to that emissary of eighties zeitgeist Rick Astley, but it began and ended at the tips of their finely sculpted quiffs.

Back in the eighties Colin Vearncombe went by the name of Black and even then seemed to carry the weight of the world on his slightly built shoulders. To me and many others of my generation he was a genuine bona fide pop star. We knew he was a pop star ‘cos he appeared on Top of the Pops cementing his status with appearances on shows such as Saturday Superstore. As odd as it sounds, that’s how you knew someone was a pop star back then. If your name and number weren’t to be found in Trevor and Simon’s Filofaxes, well you weren’t really at the races.

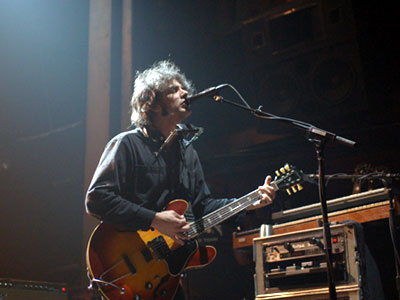

Having witnessed Colin playing a gig in his home city of Liverpool this summer, we’re now catching up to discuss his forthcoming album – his first in six years.

Lounging on a king-sized settee, wired up with headphone set looking as if he’s about to take my order for a Whopper and fries, Colin is trim, lean and alert. “I might be an old fart,” he says “but I’m not an old fart looking backwards.”

Though he’s only in southern Ireland – a (longish) stone’s throw from my abode in Liverpool – from where I’m sitting he could well be a NASA astronaut reposing in his space capsule a million light years away, such is the effect rendered by my broadband connection. The eighties’ lushness is long gone as is the trademark quiff, now replaced with a shaven head symbolic perhaps of a new found simplicity, asceticism even. Or maybe it’s just a sign of getting on. While not exactly grizzled there’s a definite air of sagacity about him, a lived in feel. If he had ever indulged in the rock n’ roll lifestyle you wouldn’t necessarily know it.

I hadn’t exactly forgotten Black, it’s just I hadn’t heard anything about him for an awfully long time, since about 1988 to be precise. I had a vague image etched into my mind of Colin on TOTP sharing the stage with an arty-looking woman playing what I assumed to be an oboe or was it a cello? Whatever it was it worked. ‘Sweetest Smile’ floated effortlessly into the top ten.

Odd isn’t it how certain moments are burned into your memory forever? Why I should remember that performance from that programme in the latish eighties is anyone’s guess. Mind you, from the same era I can still recall Henry Kelly as host of BBC’s surreal pan-European game show Going for Gold asking a bemused Dutch contestant if he wore clogs…

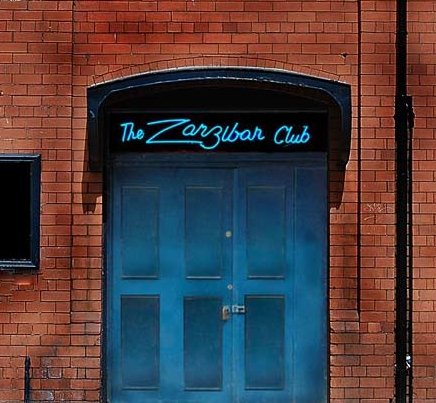

Fast forward a quarter of a century and I find myself at Liverpool’s edgy Zanzibar Club for the home leg of Colin’s recent UK tour. It’s all rather understated. Couple of stools, a mic and a guitar. No hurrahs, no fanfares, sticky floor, dodgy upholstery.

There has been a lot of water under the bridge since those heady days of 1987. After some deliberation he finally landed in Cork, south west Ireland over a decade ago (“arty” “cosmopolitan” and “breathtakingly expensive”). London had become too “bad-tempered”. Nowadays he lives on a property that could be best described as “rambling” and about as far away from metro land as one could possibly wish to be.

“I’ve got nine acres here, bought this place off some Germans who valued their privacy,” says Colin nodding his head in the direction of the half-open window behind him. “There used to be loads of Germans here in Cork. They’d seen a documentary that said West Cork would be the safest place in Europe to live in the event of a nuclear war.” Obscurity and safety then, but somewhere deep inside still the urge to reconnect.

“About three years ago I felt I needed to let people know I was still here, that I was still alive.” And so began the long trail back into public consciousness, a series of low key gigs at intimate venues. Back to the drawing board then, but surely there are bigger, grander venues out there just waiting to accommodate him?

“The truth is I wouldn’t have the nerve to do the Philharmonic in Liverpool, because I don’t know if people would be interested.” This is surprising because virtually all the ‘comeback’ gigs have sold out and the buzz of anticipation in Liverpool’s Zanzibar Club that balmy summer evening was palpable. Despite the rapturous reception, Vearncombe is cautious. The biz gave but also took away. Once bitten…

“I like my elbow room,” says Colin returning to Cork, a topic obviously close to his heart, “and eccentricity is tolerated here,” which is just as well because the Vearncombe household is not your average one. It’s more of a commune – Colin’s word, not mine – comprising Colin’s ex-wife, four sons (one of whom is adopted) and if that wasn’t enough there’s also three male students from foreign fields currently lodging with the family. Not exactly your everyday domestic situation then, but it seems to suit the Vearncombes well enough.

Colin and his ex-wife it transpires are happily living together apart. “It works surprisingly well,” says Colin. Pause. “Of course if either of us become involved with a serious partner, it would seriously alter the dynamic,” he explains before being interrupted by the shrill cries of what sounds like the mating call of the fabled Great Irish Elk. “Just a goat,” says Colin. “You get used to them up here.” If this isn’t material for a sitcom then frankly I don’t know what is.

Inevitably the conversation eventually turns to that song.

“’Wonderful Life’ was the freak – the miracle is that I was a successful as I was. I tilted my hat at being successful. I insisted on a two album contract. I figured that if it wasn’t going to work after two albums then maybe I shouldn’t be doing it.”

After the success of ‘Wonderful Life’ and the debut of the same name it all got a bit messy, doesn’t it always? The follow-up album Comedy just crept into the Top 40, a disappointment that Colin attributes to a run of poor decisions by his record label: wrong single, wrong time, wrong everything. The record company got cold feet. It was stand-off time.

“I dug my heels in with the record company. My one regret is that I stopped writing songs,” says Colin wistfully. He pauses. “Why do we dig our feet in and insist we are right? Why don’t we try to find common ground, the things that unite us?” I venture something about the benefit of hindsight, but Colin is miles away, searching for answers to riddles from long ago. “Why do we always insist on being right?” he asks with a shake of the head. A double-edged sword then success, but what about acclaim, recognition..?

“Fame was a long time ago and I don’t remember much about it. When I was famous I was certain I was going to be found out at any moment. I wasn’t any good then back then, but I got better.” Listening to all this you are left with the distinct impression that he’s glad it’s all over, happy to have had his fifteen minutes certainly, but ultimately relieved it’s over.

But fame, as Colin has found out can be a fickle mistress and peculiarly resilient one at that, popping up to surprise you when you least expect it. Not so long ago two German sisters turned up at his rural retreat convinced he was the reincarnation of their dead brother. Spooky. The frauleins apparently took some persuading to return to the Rhine and if that wasn’t bad enough a French lady also found her way to Chez Vearncombe, intent on persuading Colin to leave his wife and family and start a new life with her in France. “I wouldn’t have minded,” says Colin, “but she looked like Margaret Becket…”

“That’s a long way from your question of crowdfunding!” laughs Colin in reference to a question posed some time ago. He then goes on to explain the mechanics of what is known as a Pledge campaign: People pledge a certain amount of cash to enable the artist to produce his/her album. In return they receive extras: photos, updates, artefacts etc. More importantly they become involved. It’s a new model of making music that Colin has fully embraced. But it wasn’t always that way, at first he was uncertain, “What if no one pledges I thought – I was brickin’ it – what if, what if…”

He needn’t have worried. The campaign has really taken off and now numbers around 350 people and growing who have made pledges ranging from a few to a few hundred quid. That’s 350 individuals who Colin needs to attend to, keep in the loop. “I decided to thank everyone personally by e-mail, no copy and pasting. I just hadn’t realised there would be 350 of them!”

“And I now spend an enormous amount of time looking after the tribe, updating my pages.” This then is a long term plan, one that signalled a radical change in relationship between artist and fan, between producer and consumer. “When they get a PM from me they can’t believe it. We are purveyors of perceived intimacy, they feel they are near you.” He could have, he confesses, hung up the guitar up for good, admired the stunning views while scraping by on his twice-yearly royalty cheques. He almost did.

“At one point I thought to hell with this – I started painting again, sold a few and started to write poetry. But now I feel like the hunger has come back. I feel ready.” Returning to music, though perhaps inevitable, was not without its risks. “I was panicking about being seen as a heritage artist,” says Colin, who, you’ll not be surprised to hear, has always had a love-hate relationship with ‘Wonderful Life’. There is much more to Colin than those three and half gloriously schizophrenic minutes. He’s a serious artist, always has been. Fame, he shrugs, was just a “two year blip.”

When he’s not looking after his “tribe” or his biological family he can sometimes be found in the snug of his local pub atop a bar stool, pint in hand, treating the locals to a selection of Sinatra classics. “I’m bloody good too,” adds Colin. And when someone this modest makes such a boast, you just know it’s not idle. “Keeps you match fit for when the other stuff arrives,” says Colin borrowing yet another football metaphor. You can take the boy out of Liverpool…

“I’ve done a pretty good job of looking more successful than I am,” he says with a disarmingly wry grin. It’s apparent that he never did believe the hype not even when that hype briefly made him the darling of the music press. He confesses that he’s never had a proper job, wouldn’t know even where to start. Music is his life.

The conversation turns to bankers, Lehman brothers, Reality TV, capitalism and Irish property bubbles. Then it’s back to Liverpool FC and the team’s post-Suarez goal drought. Before I know it we have been talking for nearly two hours. “I’ve met an awful lot of unhappy rich people,” he concludes finally. And on that philosophical note our chat draws to a close.

What, I wonder out loud, should I entitle this interview, with all its twists and turns. Black is back? Too obvious. And I’ve also used his initials – CV – in a review of his Zanzibar gig (An impressive CV) in a previous article. Hmm… “How about,” says Colin always willing to help, “Portrait of a modern has-been?” He doesn’t, as you’ve probably guessed, take himself too seriously. But his music, now that’s a different thing altogether. That’s a matter of life and death.

Colin Vearncombe’s new album is out in January 2015.

For more information and to join the Pledge campaign:

http://www.colinvearncombe.com/

Dave Sedgwick