With the Everything Must Go tour in full swing, and fresh from playing two sold out dates at London’s Royal Albert Hall, the Manic Street Preachers are just as popular and influential as they were when they began back in ’86. Celebrating the 20th anniversary of the album, it was a mere 21 years ago when the bands future seemed uncertain. Following the disappearance of troubled principal lyricist Richey Edwards, the band re-emerged fighting as writer and contributor James Howell tells.

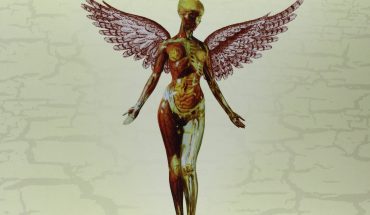

When the Welsh four piece unwillingly became a trio, the Manic Street Preachers were at a crossroads. After initially wanting to call it a day following the disappearance of their lyricist, guitarist and master of propaganda, Richey James Edwards, it was Richey’s own family that encouraged the band to continue. They returned with Everything Must Go. The fourth album, released in 1996, is not a rip-up-the-rulebook effort to break with the past nor it is a overwrought and mourning homage to their complex school friend. The Manics’ fourth album was a bold statement – we are still here.

(From L-R Nicky Wire, James Dean Bradfield and Sean Moore)

The opening track of Everything Must Go sees the Manic Street Preachers revisit old territory – the Americanisation of the UK. ‘Elvis Impersonator: Blackpool Pier’ crassly mocks the UK’s pandering to American culture, in this case with the lines “limited face paint and dyed black quiff/ overweight and out of date” – nothing new for the Manics who had taken swipes at the US of A with tracks like ‘Ifwhiteamericatoldthetruthforonedayit’sworldwouldfallapart’ from The Holy Bible. These lyrics were, of course, left behind by Edwards.

NOTE: More morbid observers of the first song on the album have noted the sounds of waves before the song kicks in and made the disturbing links to Edwards’ car being found by the Severn Bridge – but I find that too hard to stomach.

‘A Design for life’ is one of the few songs that still stands out from my childhood, despite being four years old at the time of release. The lilting and waltzing tune is memorable enough but the strength of the lyrics is something you can only reflect on and appreciate at a mature age. The chorus sees singer and frontman James Dean Bradfield roar “We don’t talk about love/ we only want to get drunk…” and through ferocious irony he looks to reclaim the notion of being working class from media representations. Oasis and Blur may have played up the media clamour of drunken and crass behaviour but new lyricist Nicky Wire had something else to say.

‘Kevin Carter’ is a typical Richey track and discusses the Pulitzer Prize winning photographer’s demise. Carter was criticised for his award winning photograph of a vulture approaching a starving young girl on the way to a United Nations Feeding Centre during a famine in South Sudan. He later took his own life. The lyrics, jagged and angry, are typical of Edwards’ style and are backed by Bradfield’s powerful, hanging chords. I have always admired the Manics for taking inspiration from wide ranging and intelligent sources. Leave Albarn to sing about boys who likes girls, the Manics have already covered Pulitzer award winning photography, what it means to be working class in the last decade of the 20th century and the smudging of west culture in the first three tracks.

Manic Street Preachers – Kevin Carter

The following two tracks, ‘Enola/Alone’ and title track ‘Everything Must Go’, are perfect examples of producer Mike Hedges’ influence and the Manics’ new sound. The producer of Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Beautiful South gave the band a more powerful and anthemic sound – long removed from the atmospheric and punk sound of The Holy Bible. ‘Enola/Alone’ is easily one of the best tracks on the album and stands to show the Wire/Bradfield partnership could still prove fruitful. It is radio friendly and upbeat, but still intelligent and reflective. Wire wrote the song after looking through wedding photos and noting the absence of Richey Edwards and their former manager Phillip Hall – who died in 1993.

“But all I want to do is live/ no matter how miserable it is” is the defining line of the album, echoing the pain the band were enduring and their determination to carry on.

The band struggled with the loss of Edwards and their fans also mourned the loss of the band’s poster boy. While Bradfield, Moore and Wire dealt with the disappearance differently (booze, DIY and home comforts respectively), all three were determined to reclaim the memory not of their fellow band member but of their friend.

‘Everything Must Go’, starts with Sean Moore’s Motown-inspired crashing drums before Wire and Moore power through a pulsating three and a half minutes of galloping bass lines and pensive lyrics. “Freed from the memory/ Escape from our history” and “I just hope that you can forgive us/…And if you need an explanation/ Everything must go” is the album’s starkest references to the end of the Manic Street Preachers as they were known. Perhaps intentionally, the following tracks ‘Small Black Flowers That Grow In The Sky’, ‘The Girl Who Wanted To Be God’ and ‘Removables’ are the three remaining tracks that included any more of Edwards’ lyrics. Some of these tracks had been worked on before Edwards disappeared, but the rich and intelligent references and influences continue shine through.

Manic Street Preachers – Enola/Alone (Live Phoenix 1996)

One new aspect of the Manic Street Preachers new direction was Wire’s lyrics. While Edwards was creative and expressive, his lyrics were always a challenge for Bradfield to set to music. Lyrics like “They drag sticks along your walls/ Harvest your ovaries dead mothers crawl” are set to acoustic guitars and harp arpeggios on ‘Small Black Flowers That Grow In The Sky’, however, the song would have had a distinctively bleaker sound if Edwards was still in the band. The same applies to the Sylvia Plath tribute ‘The Girl Who Wanted To Be God’.

Wire had never been down under when he wrote ‘Australia’ but was in fact in Torquay and the track showed his talent for musically suitable lyrics. Backed by bright and sunny music, it is no wonder the Australian Tourist Board chose to ignore the context of Wire wanting to escape from the memory of Edwards. ‘Interiors (A Song for Willem De Kooning)’ continues the theme of images and imagery from ‘Kevin Carter’ and ‘Enola/Alone’. De Kooning was an abstract expressionist painter whose Alzheimer’s caused him to forget what he was painting. It is another intellectual reference from the book-hungry Manics, but unfortunately one of their weaker efforts on the album despite a very strong vocal performance from Bradfield.

The stock and simple chord progression of the penultimate ‘Further Away’ makes the track relatively unremarkable. Wire contributes few lyrics which are stretched over three and a half minutes and echo similar sentiments to ‘Australia’. It harks back to the rock-by-numbers sound that plagued the Manics’ second album Gold Against The Soul. If ‘Further Away’ was straight-forward and formulaic, the Manics sign off Everything Must Go with a flourish. ‘No Surface All Feeling’ is a powerful song and touching way to close an album. It is musically strong with a traditional switch between soft and overdriven guitars for the chorus. The song features Edwards’ only recorded musical contribution to the album in the thunderous outro.

In the album’s final song, I still find it important to note Wire’s progression as a lyricist. He was charged with picking up where Edwards left off and when Edwards was at his most inspired. I don’t think he found his voice, or words, on Everything Must Go there is evidence of the things to come.

Words: James Howell

@jamesrhowell