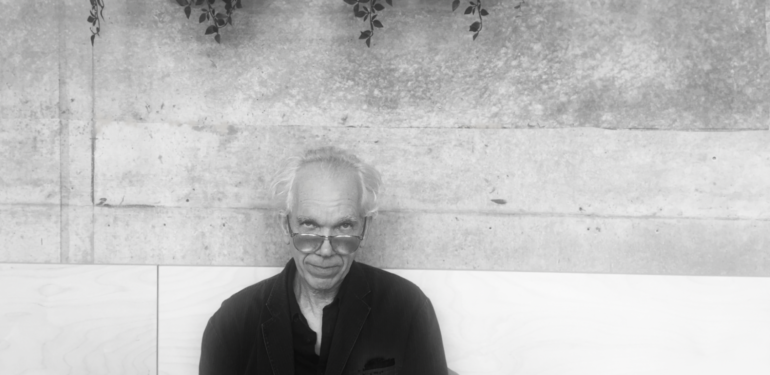

The author of Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay is a man whose very being seems imbued with an antique air. He moves, almost floats along Bold Street as if he has always walked here and always will, his communion with the city’s soul without end.

“I feed off Liverpool,” he tells me. “I’ve always been a walker, someone who leaves the house in the morning and comes back when it’s dark. I used to be a daytime drinker, so I’d go to the pub in the afternoon, a gig in the evening, followed by a late night drinking den. So I was working a fertile seam.”

But such a lifestyle is a thing of the past for Jeff Young who these days suffers from a panoply of health issues that precludes him from walking the city as he once did. “I used to walk ten or twelve miles a day. That’s what Ghost Town is, a series of walks. Putting your foot on the cobbles is how you get the pulse or the temperature of the city. It’s an exploration of place.”

He walked the city to find its beat, because only then could he hear its music. And through such music was then able to coax the memories. “The original vision of the book was to go beyond Liverpool, to go into other parts of my life – which is what the next book is going to be about. But the original plan for Ghost Town was to write a memoir that was also a travel book. But it became much more focused on Liverpool, which was the right thing to do because it made me think about how integral a place is to who we are.”

At 17, long before he knew he would become a writer, Jeff quit his job as a filing clerk on a Friday and on the Monday began hitching from Liverpool to Paris. “Loads of people I knew were forming bands and had been since punk onwards. But I didn’t really have a feel for that. I was always going to see bands but I wasn’t a musician. At school I thought I was going to be a painter, I was going to go to art school, but I couldn’t get that together. I spent a lot of time on the dole here, but eventually I dropped out and went bumming around.

“I had that creative impulse, but I didn’t know if I could write. So back then, when I was free, I thought that the living in itself was the creativity. I’d been trying to work out for quite a few years – as I was moving around Europe in the 1980s, squatting in Amsterdam where I was writing short sketches about the characters I’d known and knew – that I’d like to write, but that I didn’t really have a clue how to. I was in Paris, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Germany. I was living there because I didn’t know what to do in life.

“I was a drop out who didn’t know how to drop back in. But eventually I returned to Liverpool with my then girlfriend to see if I could write. She gave me two years to work out if I could, and after that she said she was going to South America, with or without me, in the hope that I’d get the need to write out of my system.”

But he didn’t. And she went back alone, while Jeff started putting on plays in his home town. “By the time I put on my second play I thought, right, I can do this.

“When punk happened, I remember reading a John Cooper Clarke interview in which he said that punk wasn’t necessarily about the music, but was about kicking down doors that you’d never been allowed to walk through in the past. I took that as a manifesto, as permission, as a licence to do anything, whether that’s music, theatre or writing. The world was changed by punk and not necessarily through the music. A lot of the fabric of this city has come from young entrepreneurs who learned a certain type of politics and philosophy. And that city out there on Bold Street that we’ve been walking through comes from that aesthetic.”

This was the post-Beatles era and the city was putting distance between itself and the Fab Four. “In the ’70s, no one gave a toss about The Beatles,” he laughs. “Mathew Street was our place, but we weren’t there because of The Beatles. But I have reassessed The Beatles since the Peter Jackson documentary [Get Back] because I bloody love them now.

“But during the ‘70s and ’80’s, no one gave a toss about them in the artistic community. And there was no Beatles tourist industry back then. No one here wanted to stand on the shoulders of giants, but wanted instead to be able to say we’re better than them. People back then who were getting bands together were looking more to the likes of Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell. The Beatles have been reabsorbed back into the city now, but people still find the tourism aspect of it all quite bemusing.”

Liverpool has long been a city in flux and Jeff cites Cream – the seminal nightclub that reinvented clubbing culture – as an example of a good idea ultimately wrenched out of shape by the expediency of regeneration so favoured by the fathers of the city and their developer partners. “Liverpool is still culture led, still artistically driven, but then, as ever, the establishment and the developers end up trying to steal it all.

“The grassroots creative scene, like in all cities, comes out of relative poverty, comes out of cheap living, cheap rents, out of bars and cafés that aren’t clean, are a bit grubby, a bit dodgy. But here in Liverpool, it also comes out of the Celtic, out of the Irish and the Welsh, out of being umbilically connected to Dublin and New York. The music here comes from merchant seamen coming home with blues, jazz and country records that were played in the inns, cafés and cellars. The Beatles would have heard them, and in tandem with the musicians came the painters and the Mersey poets like Roger McGough and Brian Patten.”

My own father lived in Liverpool between 1958 and 1961 and visited venues like The Cavern, the bands performing on stage then of little or no interest to him as he supped his brown and mild and looked to his own future, the birth of a new cool passing him by, his ears deaf to its squalls. Some people come to this city and are touched, bone deep, and by unexpected things.

Liverpool surprises like Naples, I say. It’s a city that stands apart from the land in which it stands with a feel all its own. “That’s a good comparison. In the 1970s, ’80s and ‘90s there was a very tangible presence in Liverpool of ‘the families’ who have links to Ireland, Amsterdam and South America. The crime lords or gangsters who operate here are still very powerful. Even though it has been caricatured in a way, there is an aspect of the city which is very on the edge. It’s a place of chancers and duckers and divers who enjoy getting the fast one over on the straights.”

But such heightened energy surely feeds a unique artistic power? “When I first started working in the arts in the 1980s when Liverpool was pretty rundown and rough and ready, impoverished in many ways, the places where you would be hanging out, socialising and drinking were the places where the painters, poets and musicians were also hanging out, but they were also the places where the dealers and the criminals and prostitutes were too. You could say it was the same demimonde and vibe of the old Soho. You took it for granted that you were going to be drinking rum in an after hours pub that was run by a Chinese gangster. But that same Chinese gangster was also putting on gigs for up-and-coming Liverpool bands. So the clubs and bars that The Beatles were playing and hanging out in were the same kind of places.

“So in Liverpool, I have never had anybody tell me No, that I couldn’t do a thing. When I first started writing, I initially started as a stand-up poet, doing poetry gigs, and then I started writing for theatre. I was getting stuff on in theatres, you know, but then if I had a play that I couldn’t get on, nobody stopped me from putting it on myself. I was encouraged to do it myself. So you got the money together, you got the people together, you hired the theatre, and you’d put it on. So that’s me, who as a kid never went to the theatre and who comes from a working class background where theatre is what other people do. There was just a sense in the community, in places where you were living and drinking, that you could do it.”

With his love for Liverpool plainly stated on the first page of Ghost Town, is he still madly in love with the city? “Yes, but it’s a rocky relationship. I think of the city as having a personality, so I do get cross with it after all these years.” Does he consider himself the last of the Mohicans? This makes him laugh. “Well, I’m knocking on a bit now and I’m not very well. But I’ve never had a mohican. But someone did call me the last of the beatniks. To a degree I feel I was born in the wrong era. I should have been living in 1920s Paris or ’50s Soho. I’m drawn to the lower echelons.”

We sit and sip green tea and coffee and address ourselves to Liverpool’s weave, a sense of timelessness that can be felt in this city more keenly than in any other. “My mum’s family were Church of England and my dad’s were Catholic, and religion still makes up a great part of the city. You can still be judged by your religion. Where I live in Liverpool, I’m on the cusp of Dingle and the other day the Orange Lodge were out marching. Usually, if you meet someone in a pub here, the two things they try and find out about you is what religion you are and what team you support. So with me they find out that apparently I’m a Protestant Evertonian.”

Liverpool is an involuting city and Jeff is a writer hanging onto its unravelling fabric when it seems no one else will, trying to save the social weave from disintegrating through the use of an impressionistic, fixative prose that echoes the lilt of his own speech. Words and music are all that count in this town.

“The best gig I’ve ever been to in Liverpool was Sun Ra at the Bluecoat in 1990. It was an axis-tilting moment, when your conventional preconception of the world was questioned. When I came out of that gig, I was tripping. Without having taken any drugs. The feeling was that he, Sun Ra, had been here and had made that whole evening happen and in doing so had changed the city. Captain Beefheart at Rotters in 1980 was another. Just seeing him in the flesh… I didn’t know what to do with that. And the first time The Fall played Eric’s, that was the John Cooper Clarke moment, when I realised I could do anything, that I could kick down the doors, just by seeing these badly dressed herberts making this extraordinary noise.”

But what of the affirmation he trusts the most when it comes to his own work? “My own. When I write something I just know in my heart that it’s good. But everything is flawed, like beauty. I try and write that book that I want to find in the bookshop. Mostly I attempt to write what I would like to read, but I’m not sure I ever succeed in that. But if anyone likes what I’ve written it’s because they’ve tuned into the same wavelength.

“My partner and our daughter tell me that I’ve lived an extraordinary life, but I don’t think I have. I just try and live an interesting life. I mean, I do feel tainted by certain jobs I’ve done, that I’ve been paid of rack of money for, that helped support me financially. But being free is important. I worked in academia, shackled to an institution for many years, and in lots of ways it was good for me because I learned a lot about myself and other people by working with students. We used the city as a canvas, as a fountain of stories and ideas. But it was an institution that was run like a business and the values of that institution are everything that I’m against. I realised that I might as well have been working for a global corporation. I took ill health retirement. It was almost as if my body made the decision for me. But I can laugh now. The key to happiness is to do what you want to do. I am happy, most of the time. Like when I was bumming around Europe. At the time I thought I liked living in squats. Money didn’t bother me. I was quite happy to be poor. I lived off the streets, I furnished my flat from the streets. That was the most free spirited I have ever been.”

He says he believes in ghosts “almost on purpose”. “I think the world is more interesting if there are phantoms in the shadows. It’s the poetics. Essentially that’s what Ghost Town is as well. It’s a haunted book, a collage, fragmentary, spliced together.” Like people, I suggest. “Well, at my age, 65, with all my health problems, I’ve recently realised that I might be closer to death now than I had previously thought I would be at this age. I’m keenly aware of my own mortality. But I’m not fearful, just rather baffled, as in how the hell did this happen?”

Jeff was recently diagnosed with skin cancer to go along with half a dozen other ailments. He takes 150 pills a week. His body is slowly failing him, but his smile is not. He remains young at heart, still that indefatigable Liverpudlian boy, full of boundless energy, thumbing his nose at the reaper. “I laughed when I was told by the doctor,” he says, grinning, the Scouse humour ever present and never far away. “I had to. I mean… it’s just fucking hilarious.”

Jason Holmes

@JasonAHolmes

Portrait by JAH

Ghost Town by Jeff Young is out now and published by Little Toller