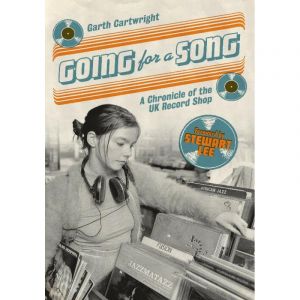

This book, Going For A Song by Garth Cartwright, is a comprehensive dérive through the rapidly vanishing terrain that is the British record shop. Once a staple of communities that acted as hubs, beacons, locales and sanctuaries for keen ears, budding musicians or those seeking like-minded wannabes and radical thinkers (London’s Collet’s acted as a recruitment centre for the Spanish civil war, Liverpool’s NEMS providing a ‘gay-friendly workplace’). They also acted as diaspora meeting points: many emigres used a record shop as a portal to ‘home’ e.g Levy’s Yiddish ‘sonic salon’ and UK-wide reggae shops’ took a defiant stance in the face of prejudice and hostility.

Featuring a typically quixotic introduction from melomaniac Stewart Lee this historical excavation encapsulates the feelings that buying physical music entails: from the thrill of finding ‘that’ record to the terror of going into the shops, the surliness and aggression of autocratic staff is a recurring feature of the book and familiar to anyone who undertook these necessary pilgrimages. We’ve all encountered one (for the ‘record’ I present Probe Records, Liverpool’s ‘Mood Boy’ a.k.a. Neil Foo Young carrying on from the scabrous Pete Burns’s ‘getting shaded’).

Beginning in 1894 (the year that Cardiff’s Spillers opened, the ‘world’s oldest record shop’) Cartwright passionately details the evolution of the form (wax cylinders and their ‘dead voices’, shellac, 78s, through to vinyl’s reign of pleasure-giving to CD’s metallic death-knell. What Paul McCartney terms ‘those exciting little black moments’ played such an integral part in worldwide cultural-identity as Cartwright superbly outlines.

These sites of cultural exchange predominantly transcended social categorising such as class (apart from HMV’s ‘toffs with the classical upstairs, the plebs in the basement’), race (although during the riots in the 1980s a siege mentality overtook some shops) and gender (several outlets were ‘manned’ by women), the dictum is that everyone’s equal in the pursuit of music.

The cast of thousands number such sellers as Andy’s Records (where a young Chris Morris worked), Belfast’s Good Vibrations whose Terri Hooley provided a unifying space during the Troubles, Transat (‘like Howard Carter in Tutankhamen’s tomb’), Rock On and musical luminaries and renowned recordphiles as Bowie, Elton John, Bob Dylan (who performed as ‘Blind Boy Grunt’ in London’s Dobell’s in 1963), The Moody Blues and Morrissey who typically articulates the educative power shops and records possess: ‘Manchester’s Paul Marsh was my Eton’. Cartwright captures these times and memories that remind of the cultural importance and symbolic capital that the consumption of music once provided.

The architect Richard Sennett writes of a dialectical tension between ‘ville’ and ‘cité’. ‘Ville’ is the physical actuality of the place, ‘cité’ the life that is led in that place’ this tension embodies the psychic realm of the record shop none more so than in the case of Ladbroke Grove’s Plastic Passion whose two proprietors (‘the Two Bills’) bitterly fell out and in a move worthy of Steptoe & Son split the premises down the middle. The lure of the prize and the behaviours shaped by the pursuit is wondrously captured by Cartwright with the disappearance of these ‘democratic spaces’ symbolic of other facets of cultural decay such as the music venue, weekly music press, local pub and the weekly television talking point.

An over-arching theme that punctures the romanticism is that for most of the entrepreneurs it was strictly business: product = money. Vulture capitalists (Richard Branson’s initial catering to the cognoscenti eventually becoming the epitome of ‘never trust a hippy’) exploiting the cultural capitalists’ needs and wants as identikit high street emporiums with their corporate mentality (HMV/Our Price/Tower Records) systematically squeeze the passion out. London’s Soho a pale shadow of its former self as music hub a case in point.

However, for the most part, these are tales populated by like-minded music-seeking obsessives, this is more than a way of life, music and its rituals providing kinship, identity formation and reasons for living, an altruistic desire to discover and provide these artefacts essential to personal development.

The book is not only a history of the shops but also the myriad characters that owned, frequented them (‘N.M.E. writers flogging promos for beer’), the production and distribution, the mechanics behind the magic. This progression from selling to producing is also examined as shops became labels: Beggar’s Banquet, Geoff ‘Rough Trade’ Travis’s Marxist ethos drove his desire to ‘control the means of production’, punk’s Small Wonder and their seminal Crass releases, ‘disco Granny’ Jean Palmer’s Groove Records that championed acid house, techno to the emergence of dubstep in Croydon in the early 2000s.

His delight at unearthing these histories and characters is only soured by the sad demise of these once relevant foci, as sites of transaction and exchange become replaced by online vendors dealing in demystified commodities, negating the pain of pursuit/the rewards of ownership which were/is part of the pleasure. Instant gratification is no substitute for unquenchable desire, no one ever learned a thing from having it all. As empires rise and fall in parallel with musical trends (jazz to skiffle to psychedelic to Northern Soul to Dub to punk …) ultimately music has depressingly ended up as a drip-fed backdrop to sell ‘accessories’ such as detergent and condiments.

Cartwright manages to locate the survivors, those die-hards resolute in the face of technology’s over-provision attention indigestion services. This thoroughly researched psychogeographical labour of love is an antidote to these hyper-consumptive times of streaming, downloading, quick fix digital droids whose ‘music-to-go-on-the-go’ technonanism embody Marshall McLuhan’s dictum ‘the medium is the message’. The book is also a rejoinder to the ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ shenanigans of Record Store Day when scarcity equals value equals exploitation. Plus, we call it ‘shop’ in Blighty, yeah?

As dub-king Dennis Bovell laments Clapham’s Third World both dryly and saddeningly ‘… it still exists, but, it’s been downsized while Costa Coffee has been upsized … people today will pay for coffee, but not for music. The internet killed the reggae shop. If people can download tune to their phone they won’t ever buy a record’.

33/45

Kemper Boyd

@dissapointon